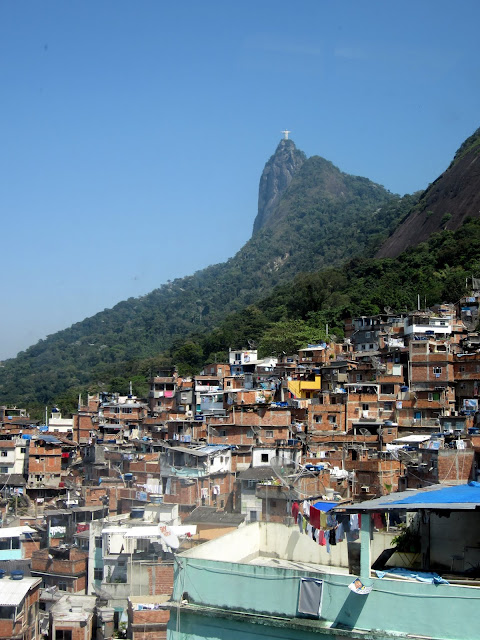

A favela is what is often inelegantly called a "shanty town", but from an urban planner perspective these area are informal settlements. They are part of the built environment that were built without architects, planners, or engineers and instead with the materials on hand and expertise developed through experience. They are also notable because favelas are usually located on hillsides that the formal city ignored. While I was in Rio, I wanted to visit Santa Marta, which is a favela that I studied while in Sweden as part of a human settlements and housing course. From Scandinavia, I had already studied the maps, structures, and satellite images of the area, along with news papers and research on Santa Marta and the socioeconomic issues involved. I wrote a paper on the place, but I had never been there. This was a chance to see it for myself and touch what I studied.

There are some issues involved with visiting a favela. The first and foremost is whether you should visit one at all. Favelas exist because of economic inequality and as a foreign tourist, you stand on the privileged side. In many ways the economic disparity that causes favelas to exist is also the reason you are able to enjoy Rio to the extent that you do. Your hotel room in Rio for a single night is likely more than half a month of rent in a favela (which is between $75-$250 a month, according to here). When you visit a favela, you are seeing a side of Rio that is foreign to you. It is another city and although some favelas (such as Santa Marta) are becoming safe enough to visit independently, your presence in this tight knit community is almost a transgression. The streets and stairs in the favela were built by the the people who live there, not by the government, and you are using them. It would be easy to come into the community as a poverty tourist, someone who engages the community as an exploitative voyeur. Many of the tourist that now visit favelas are likely motivated either by a romanticism of poverty, a sense of curiosity similar to when you visit a zoo, or in the worst of cases, a desire expressed or unexpressed to experience schadenfreude upon seeing the "others". Our intent was none of these, and we hope that our intentions were understood through our actions and respect for the place.

On other side of this question, is it right to simply ignore these places and the social division in Rio? Rio de Janeiro is a city of contrasts and experiencing the community and place of a favela is a way to gain balance in your perspective. It is also a way to balance the image of favelas, portrayed in the news and media, with the realities of the favela. By being there, you can gain a better understanding about what is true and what is drama. This is something that can have value if it is done right. In our case, we hired a local guide named Gilson Fumaça because we felt that the jeep tours didn't give us enough assurance that what we paid would go directly to the community. He is from the favela and works there when he doesn't have a tour going on. He is part of the Rio Top Tour program, which helps train favela residents to offer their own tours of the favela without having to go through a middle man. Even though there was a language (helped dramatically by another guide that decided to join us/took pity on us), one that that Gilson was able to do was to make us more accepted within the community. As we walked, it became clear that he knows the community and is on good terms with seemingly everyone. He would great an old lady who would go from at first wary of us to smiles, after a few words and a smile from our guide. After the tour, both of us (I was there with my other planner friend) felt that even though we weren't able to ask as many questions as we would have liked due to us not speaking Portuguese, having Gilson show us around was the right way to visit. Today, after visiting, I would say that this favela, Santa Marta, is safe enough to visit independently, but I remember seeing some other unguided tourists and it was clear that they were not really welcome from the looks they were getting. Tourism in the favela is still a debate.

After the break, many more pictures from the favela and my observations of the favela and what it means for the city.

|

| From Sugarloaf at a night towards Botafogo |

A few years ago, Santa Marta became one of the first favelas to go through a process called "pacification", which is an initiative by the government to force out drug gangs and start a process of formalization, wherein the favela is meant to become part of the officially recognized city. The process is effectively a take over by force with the goal of uprooting drug gangs, which in other favelas are de facto the law. These drug gangs are heavily armed and conflicts between the different gangs, as well as with the police, are one of the primary sources of violence. Santa Marta became a "model favela" and part of that has been some significant investments in the area: A new road connects the city to the top of the favela, where the police station is. A funicular ("Plano Inclinado") was built on the right side of the favela, which is was meant to make it easier for residents to reach the top. The funicular also serves as a vital infrastructure link for trash (headed down) and building materials (headed up).

|

| This smaller utility stop is used only for trash collection. |

|

| Trash coming down. Employees and trash are the only ones allowed in there. |

The ride up takes about 15 minutes... when it is working correctly. There was some level of disillusionment with the funicular, which was said to be frequently out of service or shut down for maintenance. In fact, on our ascent, the car came to a sudden stop and we were stuck for 5-10 minutes while we waited for it to kick in again. The bad news for residents is that without this link, the only other option is to walk up the stairs from the bottom to the top (or drive in along the road). Another limitation is that at peak hours, the system is overwhelmed (such as in the mornings with children headed to school or in the evenings as people off of work head home). One of the interesting side effects of the lack of a reliable way to get to the top is that the top of the favela was younger on average than at the bottom. As mobility deteriorates with age, older residents move down the hill and the youngest are at the top.

At the top, Ipanema and Leblon are visible in the distance. To give an idea of the disparity between the favela and the neighborhood directly next to it, I asked our guide how much it would cost to buy a home in the favela. About 50,000 Brazilian Reals, which is just shy of $25,000 USD. An apartment on the main road by the favela (about 3 blocks from the lowest level)? 500,000 Reals, or $250,000 USD. In addition, Santa Marta is actually one of the more highly sought after favelas because it is so close to the tourism and service sector jobs, which is where many favelados find work in the formal economy. They are the maids in the hotels or the staff in the kitchen and the favelas play the role of providing affordable housing for the workforce that enables the more luxurious side of Rio.

The very top is marked by two distinct features, besides the top of the funicular. The first is the blue UPP ("Unidades de Polícia Pacificador", or Pacifying Police Unit) station, which is not a place that you want to end up. The interior is stark and bare, but the officers there were friendly (if not well armed). The police from here have about a dozen cameras that monitor some of the common areas of the favela. The wall beside the station, which is also the first picture in this post, is pockmarked from small arms fire. When asked whether we could be in this area before the police, my guide laughed. Directly beside the police station is also the football field where youth can play, and then the upper most part of the favela ("Pico do Morro").

This upper most part is currently the epicenter of a political struggle between residents and the government. As we stepped off the funicular, a TV camera was set up for interviewing one of the residents in this area. In recent years, the government has determined that the slope where these homes are presents a risk to the rest of the favela. There is a risk that under heavy rain, the slope may destabilize and cause a landslide that could kill many in the community and cause immense damage. The government wants to evict the residents and perform geological work to stabilize the top of the hill. Residents counter that if the top is unstable, then the whole favela is just as bad. Why just this part of the favela? The same line of thought could be applied to any home in the favela (or any favela on a hill). One of the views expressed is that Santa Marta has been paradoxically punished for cooperation with officials, which has included limiting the growth of the favela into the ecologically sensitive forests next to it and accepting the UPP and formalization process. Other favelas, they rightly point out, have aggressively expanded in disregard for governmental plans and is not being targeted in the same way for eviction/destruction of their homes. The issue is broken trust, and I can't see an easy way out of this for either side. There may be legitimate reasons to worry about the slope, but residents have reason to question whether this is strictly necessary.

From the top, you walk down. For me, this was the most interesting part because I was able to see first hand what had until now been something only seen through the screen, similar to how you are experiencing Santa Marta now. Looking back, there were some areas that we got right, and other areas that we weren't able to see from afar. One thing that I missed was the degree of difficult that the pathways presented. The paths wind and weave throughout the favela over every bump, creating very uneven terrain. We also underestimated the pace of formalization in the favela. The electric company has already moved into the favela and while we were walking down our guide even picked up his electric bill from an employee of the company that we ran into.

About half way down is one of the main sights of the favela: The Michael Jackson statue. Pictured here with our guide Gilson, Michael Jackson is credited for helping put the favela on the map with the music video "They don't really care about us", which was filmed in part in Santa Marta. The statue is also part of the recent changes in the favela and was installed in 2010.

What do we learn from an experience like this and what sort of lessons should we take away from it? I think the most important thing is to recognize that the systems at work in the favela are actually similar to the ones that we find much closer to home, even if the contrast created by the greater economic disparity isn't quite as stark in our own neighborhoods. Santa Marta is going through a process of gentrification which brings with it both the benefits from the gradual demarginalization of the area and draw backs that comes with gentrification. The same concerns about the loss of affordable housing and the right of people to live near where they work (a common theme in Seattle, for example), is at play here in Santa Marta. The same patterns of economic disfranchisement and crime that we have seen in many places and communities in the United States is the same driving force here in many cases. There is a commonality between what is happening here and what is/has happening in other places in the world, including in a neighborhood near you.

Interested in visiting yourself? At the base of the favela by the bus stop, there is a yellow booth which is part of Rio Top Tour, a government program that helps connect favela residents trained as guides and people interested in getting engaged in this subject. If you are interested in a more in depth look at the ethics of visiting a favela, please see this working paper from Boston University.

No comments:

Post a Comment